Rhetorical Précis Writing

A rhetorical précis analyzes both the content (the what) and the delivery (the how) of a unit of

spoken or written discourse. It is a highly structured four-sentence paragraph blending summary

and analysis. Each of the four sentences requires specific information; students are expected to

use brief quotations (to convey a sense of the author’s style and tone) and to include a terminal

bibliographic reference. Practicing this sort of writing fosters precision in both reading and

writing, forcing a writer to employ a variety of sentence structures and to develop a discerning

eye for connotative shades of meaning.

Take a look at the overall format

1) Name of author, (optional: a phrase describing the author), genre and title of the work, date in parentheses (additional publishing information in parentheses); a rhetorically accurate verb (such as "assert," "argue," "suggest," "imply," "claim," etc.); and a THAT clause containing the major assertion (thesis) of the work.

2) An explanation of how the author develops and/or supports the thesis, usually in chronological order.

3) A statement of the author's apparent purpose followed by an "in order to" phrase.

4) A description of the intended audience and/or the relationship the author established with the audience.

1) Name of author, (optional: a phrase describing the author), genre and title of the work, date in parentheses (additional publishing information in parentheses); a rhetorically accurate verb (such as "assert," "argue," "suggest," "imply," "claim," etc.); and a THAT clause containing the major assertion (thesis) of the work.

2) An explanation of how the author develops and/or supports the thesis, usually in chronological order.

3) A statement of the author's apparent purpose followed by an "in order to" phrase.

4) A description of the intended audience and/or the relationship the author established with the audience.

Now take a closer look:

1. THE FIRST SENTENCE identifies the essay's author and title, provides the article's date in

parenthesis, uses some form of the verb says (claims, asserts, suggests, argues—) followed by

that, and the essay's thesis (paraphrased or quoted).

EXAMPLE: In "The Ugly Truth about Beauty" (1998), Dave Barry argues that "...women generally do not think of their looks in the same way that men do" (4).

EXAMPLE: In "The Ugly Truth about Beauty" (1998), Dave Barry satirizes the

unnecessary ways that women obsess about their physical appearance.

2. THE SECOND SENTENCE conveys the author's support for the thesis (how the author develops the essay); the trick is to convey a good sense of the breadth of the author’s support/examples, usually in chronological order.

EXAMPLE: Barry illuminates this discrepancy by juxtaposing men's perceptions of their looks ("average-looking") with women's ("not good enough"), by contrasting female role models (Barbie, Cindy Crawford) with male role models (He-Man, Buzz- V. Stevenson and M. Frerichs, AP Language PHHS, San Diego, reprint date: 5/24/2010

3. THE THIRD SENTENCE analyzes the author's purpose using an in order to statement:

EXAMPLE: He exaggerates and stereotypes these differences in order to prevent women from so eagerly accepting society's expectation of them; to this end, Barry claims that men who want women to "look like Cindy Crawford" are "idiots"(10), implying that women who adhere to the Crawford standard are fools as well.

4. THE FOURTH SENTENCE describes the essay's target audience and characterizes the author's relationship with that audience—or the essay's tone:

EXAMPLE: Barry ostensibly addresses men in this essay because he opens and closes the essay directly addressing men (as in "If you're a man...”) and offering to give them advice in a mockingly conspiratorial fashion; however, by using humor to poke fun at both men and women’s perceptions of themselves, Barry makes his essay palatable to women as well, hoping to convince them to stop obsessively "thinking they need to look like Barbie" (8). Put it all together and it looks darn smart:

In "The Ugly Truth about Beauty" (1998), Dave Barry argues that ". . . women generally do not think of their looks in the same way that men do"(4). Barry illuminates this discrepancyby juxtaposing men's perceptions of their looks ("average-looking") with women's ("not good enough"), by contrasting female role models (Barbie, Cindy Crawford) with male role models (He-Man, Buzz- Off), and by comparing men's interests (the Super Bowl, lawn care) with women's (manicures). He exaggerates and stereotypes these differences in order to prevent women from so eagerly accepting society's expectation of them; in fact, Barry claims that men who want women to "look like Cindy Crawford" are "idiots" (10). Barry ostensibly addresses men in this essay because he opens and closes the essay directly addressing men (as in "If you're a man...”) and offering to give them advice in a mockingly conspiratorial fashion; however, by using humor to poke fun at both men and women’s perceptions of themselves, Barry makes his essay palatable to both genders and hopes to convince women to stop obsessively "thinking they need to look like Barbie" (8).

Barry, Dave. "The Ugly Truth about Beauty." Mirror on America: Short Essays and Images from Popular Culture. 2nd ed. Eds. Joan T. Mims and Elizabeth M. Nollen. NY: Bedford, 2003. 109-12

NOTES TO LOOK OVER

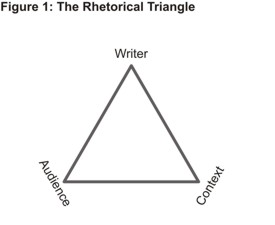

^^^^ The Rhetorical Triangle (Aristotle)

What in the World is Rhetoric???

Well, according to the book, rhetoric is "a thoughtful, reflective activity leading to effective communication, including rational exchange of opposing viewpoints." This to me sounds like the act of opening your mouth and conversing, or perhaps, debating with someone.

KEY ELEMENTS:

-Context

The context is the occasion that the essay/speech was given. This can be somewhat like the setting of a story, and by knowing this, you can properly assess who the intended audience is and whether or not the context increases the effectivity of the piece.

-Purpose

The goal that the speaker/writer/author wanted to achieve. This coincides with the context and allows the writer to choose the best possible audience in which to present the piece.

-Thesis/claim/assertion

This could be the

-Subject

What the piece is about, the topic, y'know... so the author should have a very good grasp on what he/she/it wants to talk about in order to express the ideas/comments thoroughly and with as much consistency as possible.

Ethos:

Ethos is the character of the writer or the speaker. Good ethos is when the writer presents his/her/itself as a classy individual while also coming off as "credible and trustworthy". Allowing the audience to connect with the author is something that really helps push the point across and deliver the best results for giving a great speech/rhetoric.

Logos:

Logos is the appeal to logic/reason, by offering the audience clear and easy-ro-understand ideas that make as much sense as possible, while remaining rational. Presenting a main idea in a concise manner, showing another side/counterargument, credible statistics and facts, and/or expert testimony. (See "Things Fielding told us to include in Persuasive Essays.")

Pathos:

Pathos is the appeal to emotion. While this isn't something that should be emphasized as it can come off as propaganda which is not what you want. Appealing to the emotions means using vivid word choice that can easily stimulate the readers' thoughts and using the first-person perspective.

The Classical Arrangement of Rhetoric:

1. Introduction (exordium)

-Brings the reader into the discussion, emerging them into the world of rhetoric. Introductions can be a couple short sentences, or several lengthy paragraphs (pages...!). Drawing the reader in is important (hook) and presenting the main idea (thesis statement) and stating the order of development. Normally, this is where the author would establish ethos.

2. Narration (narratio)

-Factual information is presented and background information give the reader that much more insight into the subject. This is typically when you would begin to appeal to logos, yet it is smart to consider appealing to pathos as you are inclined to evoke an emotional response form the reader so that they can firmly decide on your opinion with the facts and statements you present.

3. Confirmation (confirmatio)

-A large portion of the writing that sets up the proof of your argument and why the audience should agree. The details in this section should be strong and thorough, while making the biggest appeal to logos in this section.

4. Refutation (refutatio)

-This part of the writing takes a look at the other side of the topic, the counterargument, if you want to call it that. Used as a "bridge between the writer's proof and conclusion" but also as appeal to ethos, as the audience can see that you are passionate enough about your subject that you chose to research both sides to get as informed as possible.

5. Conclusion (peroratio)

-Closing the essay, appealing to pathos one final time as well as connecting with ethos set up in the beginning of the piece. Instead of repeating what has already been said (guilty of this on several occasions... :l ), the writer's ideas should all get compacted into one and "answers the question, so what?" The last words are usually the ones that the audience is going to remember, so make them count. Throw it all out on the table and sum up the essay with as much intelligence as possible!

Patterns of Development:

Authors can change their arrangement by writing in order of purpose. Each method of writing purposefully has its own way of organizing thoughts and piecing together all the little eccentricities neatly and professionally.

Types of Essays We'll Be Writing:

Narration: Tells a story and recounts tales of slaying dragons and mystical creatures. Not really, but narration is typically a recollection of previous events, usually chronologically, or as a means to enter into the main idea of an essay.

Description: Much like narration and just as detailed (if not, more so), but the details focus more on the sensory responses from the readers. These include, the ways things taste, the sounds around the writer, textures and feelings, sights, colours, setting up an atmosphere for the piece. The descriptive language is a way to help make thoughts more approachable to the readers and helps in being more persuasive.

Process Analysis: An explanation. A how-to. The steps on how to achieve something or engage in a process. These can best be found in (according to the book) self-help books. Because these are going to help the way someone lives or acts, you must be as clear as possible in the instruction with smooth, flowing transitions as to not miss a step or confuse anyone.

Exemplification: Hopefully, this is readable... Facts, examples, testimonies are all ways to make an idea complete. With complete ideas, come more acceptable readers and easier persuasion.

Comparison and Contrast: Highlighting similarities and differences in an organized fashion allows clear presentation of points that can be easy to digest for the audience. With careful analytics, the author can find interesting tidbits of information that could open up ideas to readers that otherwise couldn't be achieved, as well as highlighting both sides of an argument or multiple angles of a topic.

Classification and Division: Sorting information into how topics go together and why. Connections can be made between things that are seemingly unrelated and thus, like Comparison and Contrast, can reveal difference aspects to the reader that otherwise were unknown.

Definition: Defining something can allow more points to come through and allow "meaningful conversation". Example: (See what I'm doing here?) Let's talk about how awesome alligators are. But before we do this, we must DEFINE what counts as "awesome". Perhaps a dictionary definition.

Cause and Effect: Causes and Effects. Self explanitory... "The effects that result from a cause is a powerful foundation for argument." Seems legit.

No comments:

Post a Comment